The success of Planet of the Apes (1968) demanded a sequel and although Ted Post’s follow-up has been much derided in some quarters it’s probably not as bad as you might remember. Certainly with its psychic, nuclear bomb-worshipping mutants, it’s a trashier and more pulpy affair than the original, but it’s still an undervalued film which boasts another extraordinarily downbeat ending.

In a prologue, Taylor (Charlton Heston) disappears into thin air deep in the “Forbidden Zone” after he and Nova (Linda Harrison) suffer strange hallucinations. Nova tries to make her way back to Ape City to find Zira (Kim Hunter) and Cornelius (David Watson, replacing Roddy McDowall who was busy in the UK directing The Ballad of Tam Lin (1970)) and en route encounters Brent (James Franciscus), another astronaut stranded on the planet of the apes after being sent on a rescue mission to locate Taylor and his crew. In Ape City they are taken in by Zira and Cornelius but elsewhere militaristic gorilla General Ursus (James Gregory) is calling for an expedition into “Forbidden Zone” against the objections of Dr Zaius (Maurice Evans). Brent and Nova flee and find themselves in a the ruins of New York where a group of telepathic, radiation scarred humans have formed a cult worshipping the Alpha Omega doomsday bomb. Brent is reunited with Taylor who has been imprisoned by the cult, just as the apes arrive. Wounded in the ensuing battle, Taylor falls on the control panel of the bomb, destroying the world.

The first half of Beneath the Planet of the Apes threatens to be just a re-run of the first film with its time-displaced astronaut struggling to come to terms with what has happened to the world. Where it really scores is in the second half where sanity and common sense are thrown to the wind and the film transforms into a wild descent into madness, a trip into a subterranean nightmare where radiation scarred mutants mentally torture passing humans, create horrifying hallucinations to frighten the approaching apes and sing hymns to a nuclear weapon. The latter half of the film is strikingly original and ultimately elevates a run-of-the-mill sequel into something far more interesting. One of the most fascinating aspects of the Planet of the Apes series is that each film goes off in a new direction, always trying out new ideas. They don’t always work and Beneath gets off to a shaky start by retreading familiar ground but when they’re as audacious as they are here they can be highly effective.

The most interesting aspect of the first half is its more vivid exploration of the strict caste system that informs ape society. It’s a more complex set-up than were led to believe in Planet of the Apes with with tensions running high between the war-mongering gorillas, the more religiously and philosophically inclined orangutans and the liberal, intellectual chimpanzees. In the second half, the mutant New Yorkers are revealed to be every bit as religiously and socially intolerant as the apes, both sides using their twisted beliefs as an excuse for violence and repression. Taylor’s dream, in the first film, of finding something better than man elsewhere in the universe has soured considerably by the time he falls, wounded and dying, on the detonator and finally brings the whole madhouse crashing down.

If anything, the ending of Beneath the Planet of the Apes is even bleaker than the original. Planet had ended with a shock to the system but Beneath ends with the ultimate gut punch and seemed to signal the end for the still young franchise. A final brief voice over (by an uncredited Paul Frees) is a chilling coda – the screen flares to white as the Alpha Omega bomb explodes, then fades to black as Frees intones “In one of the countless billions of galaxies in the universe, lies a medium-sized star, and one of its satellites, a green and insignificant planet, is now dead.”

British writer Paul Dehn takes over the writing duties here and remained with the series for the next two films and brings with him even more cynicism than Michael Wilson and Rod Serling brought to Planet. Note the telling use of the word “insignificant” in that closing voice over. The petty, if violent, squabbling between the apes and the mutants despairingly suggests that after all the calamities that have already befallen this blighted planet, no-one has learned a thing and perhaps, in the end, Taylor’s actions (whether he deliberately activates the detonator or simply falls on it as he dies is a point still open to debate) seem like a mercy killing.

Dehn’s script gets in a muddle over details seemingly only half-remembered from the first film. The year here is given as 3955 (a date that would remain in play throughout the sequels) whereas it was 3978 in the first film and Zaius refers to Zira and Cornelius as a pair of psychologists, where the latter was an archaeologist the first time around. You have to wonder too what a nuclear missile silo was apparently doing beneath Grand Central Station. It’s not a particularly subtle script (Dehn would fare better in later films) and the satire isn’t as potent as it was in the first film (it tips its hat to the police disruption of civil rights protests that became increasingly violent in the late 1960s and early 70s) but it’s not without its charms.

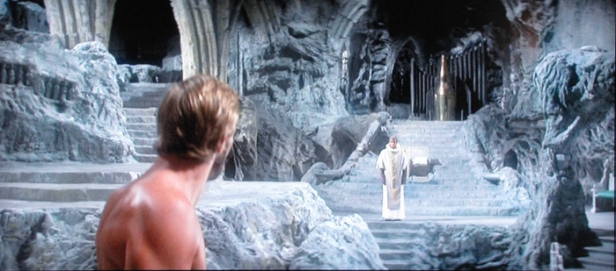

The list of ways in which Beneath fails to match up to Planet is long but look at the things it gets right: the New York sets, recycled from Hello Dolly! (1969), are creatively used, it remains as vehemently anti-war as Planet, the scenes in the underground city have a surreal intensity that the earlier scenes notably lack, the image of the gleaming Alpha Omega bomb amid the ruins of New York is startling and wonderfully absurd, and the mutant ceremonies (“May the Blessings of the Bomb Almighty, and the Fellowship of the Holy Fallout, descend upon us all. This day and forever more”) and hymns (“all things bright and beautiful, the Lord Bomb made us all”) are hilarious.

Religious symbolism abounds. The twisted mutant ceremonies obviously, but elsewhere there are nightmare visions of gorillas crucified upside down amid walls of flame and a gigantic statue of the apes’ “god”, the Lawgiver, bleeds profusely in a parody of Christ’s stigmata.

Performances are a real mixed bag this time. Heston isn’t around long enough to make much of an impact (it’s been suggested that he only agreed to return if Taylor was killed off) and Franciscus isn’t much of a replacement – he’s simply there, going through the motions without bringing any passion or conviction to a nothing role. Evans and Hunter are great again as Zira and Zaius but although David Watson does his best he’s no Roddy McDowall. James Gregory takes the acting honours, fantastic as the rabble-rousing gorilla leader Ursus (“the only good human is a dead human”).

Of course it’s not as good as the original. After a string of exclamation marked box office disappointments (Star! (1968), Hello Dolly! and Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970)), 20th Century Fox slashed the film’s budget in half and it shows, never more so than in the crowd scenes where ape extras are notably wearing cheap masks rather than John Chambers’ more elaborate – and therefore more costly – make-ups. Post isn’t as dynamic a director as Schaffner and Leonard Rosenman score is more traditional and therefore less effective than the startling, atonal racket Jerry Goldsmith supplied for the first film.

And yet for all that it’s a film that still entertains. Maybe it’s just a fondness for that nihilistic ending that makes the film linger more affectionately in the memory than it probably deserves. But there’s undeniably something about the insanity of the mutant bomb-worshippers that makes Beneath the Planet of the Apes an endless source of fascination. It’s not the best the series would have to offer, but nor is it the worst – that dubious honour is held by 1973’s Battle for the Planet of the Apes. But it’s still a worthy if under-rated addition to the Apes franchise.