Hammer’s first dalliance with Black Arts came in the unassuming shape of Cyril Frankel’s The Witches which, despite a screenplay from Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale, proved to be a dull adaptation of the novel The Devil’s Own, written by Norah Lofts using the pseudonym Peter Curtis, a tale of Home Countries witchcraft that promises a lot more than Frankel can deliver. Its roots lie with its star, Joan Fontaine, who had bought the film rights to the novel in 1962 and it wound up at Hammer when it came to the attention of their funding partners Seven-Arts. Its failure at the box office came as a bitter blow to Fontaine who never worked again.

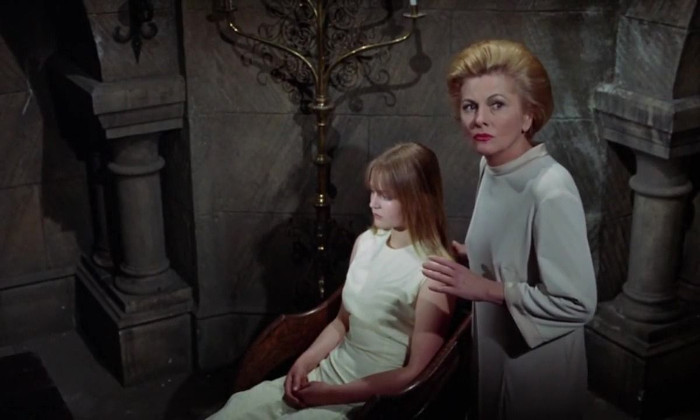

English schoolteacher Gwen Mayfield (Fontaine) returns from Africa to recover from a nervous breakdown and takes up a job teaching at a small school in the village of Heddaby run by the Reverend Alan Bax (Alec McCowen). At first it seems the idyllic job she needed to complete her recovery, but strange things are afoot in the sleepy village. Bax may not be a minister at all, and his school turns out to not to be affiliated with a church as he claims. Bax’s sister, Stephanie (Kay Walsh), dismisses his eccentricities as “a harmless pretence” while Bax cryptically claims it to be “for security.” Two of her students, Ronnie Dowsett (Martin Stephens) and Linda Rigg (Ingrid Boulting, step-daughter of director Roy Boulting, here using the name Ingrid Brett) have become romantically involved, a fact that seems to set the villagers nerves on edge and Ronnie confides in Gwen that Linda is being abused by her grandmother (Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies). Gwen slowly comes to suspect that Granny Rigg is a witch, especially after Ronnie falls ill and a doll he gave to Linda is found in a tree with pins stuck in it. And it turns out that she’s right, there is a witch exerting control over the villagers – but it’s not the person she first suspected.

There are a lot of good ideas here, as you’d expect from a Nigel Kneale script, but Frankel’s listless direction and the weird tonal inconsistency does nothing for them. Fontaine gives it her best shot but frequently looks uncomfortable and out of place and is easily outclassed by Kay Walsh as the leader of the village coven. Bax even manages to go some way – though not far enough – to redeem the fantastically silly finale which sinks the film stone dead.

In retrospect, The Witches (released in the States under the novel’s original title) has been lumped in with the “folk horror” films, but it seems more of a piece with Kneale’s ongoing project to explore the clash between faith and rationalism. It’s been suggested that it was originally Kneale’s plan to lampoon the coven of witches and their practices and believes and we can see some of that in the overwrought finale in which Bax oversees a ludicrous ceremony that involves her wearing a flaming (well, flickering…) headset, spouting cod Latin and watching on as the Mummerset villagers douse themselves in fruit juice and eat what appears to be worm infested mud and engage in a modern dance routine. If the climax isn’t a deliberate, last minute and very dramatic change of tone, it’s one of the most farcical moments in any Hammer film. It’s honestly hard to tell. Kneale was reportedly unhappy with the finished product (he often was) and in this case it’s really not hard to see why.

The rest of the plot is just as weirdly constructed, and the film often plays as if last minute revisions were made to the script without much thought being given to what those changes would do to the ongoing narrative (the ending is notably abrupt). Granny Riggs, fantastically played by Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, is initially being set up as the force behind the supernatural happenings afflicting the village, but she largely disappears from the plot once suspicion shifts to the Baxs, popping back up again only during the delirious climax. The most unsettling moment in the film comes when Gwen wakes to find herself in a nursing home, apparently having been there for weeks. There are other nice touches here and there – the hideous doll flopping about on a cabalistic sign (it turns out to be something entirely mundane but it’s still an unsettling image) is a particularly memorable image but it rather marks the point at which the intriguing part of the film is about to collapse under the weirdness of that silly and over-long finale.

The Witches is a frustrating film. In the hands of a director more sensitive to the subject matter like Terence Fisher, or maybe even Freddie Francis, all of this might have worked, and the film might be better thought off today. Frankel (who had previously made the makes bice use of the cosy locations in Hambleden, Buckinghamshire and stages some of the early scenes nicely. But he loses control of the film in the hysterical finale, the key moment that a genre master like Fisher might have handled with much more aplomb.

Hammer had a lot more luck in the Satanism stakes when they turned their attention to Dennis Wheatley and adapted two of his novels into Fisher’s excellent The Devil Rides Out (1968), widely regarded as one of the company’s finest achievements, and the less well-regarded but still fascinating To the Devil a Daughter (1976), directed by Peter Sykes.