Fritz the cat began the first of his nine lives as a character in a self-published comic book, Cat Life, created in 1959 by the famed underground comics artist Robert Crumb. Fritz, a hedonistic, free-spirited adventures in all areas of sex and drugs, was inspired by Crumb’s own pet, Fred and was soon appearing in underground and pro-zines like Help!, Cavalier, Head Comix and others. The character was soon a big hit in the counterculture even though his actual appearances were relatively few (more stories, not originally for publication, were published in the 70s and 80s).

One of his fans was the animator Ralph Bakshi who had spent ten years from the age of 18 toiling at Paul Terry’s animation company, Terrytoons, surely the most anodyne of all of the Hollywood cartoon houses. After knocking out innumerable Mighty Mouse, Heckle and Jeckle and Deputy Dawg shorts, he moved to Paramount to head their animation division but only managed to make four shorts in eight months (The Fuz (1967), Mini-Squirts (1967), Marvin Digs (1967) and Mouse Trek (1967)) before the operation was shut down. He set up Bakshi Productions and after taking over a couple of existing television series (Rocket Robin Hood (1966-1969) and later episodes of Spider-Man (1967-1970)), decided to branch out into feature films. After his first script, Heavy Traffic, was abandoned when he was advised by his production partner Steve Krantz that no-one in Hollywood would touch it (it was eventually made in 1972), Bakshi suggested adapting Fritz the Cat instead. Even then, it wasn’t plain sailing – Warner Bros, originally agreed to fun the film but got cold feet but when their executives caught sight of the initial footage, they pulled out and Bakshi had to get alternate funding from distributor Jerry Gross and his Cinemation Industries company.

The result is a film which, today, is far more interesting for the place it earned in animation history than for what it actually is. It was the first film to be awarded an ‘X’ certificate by the Motion Picture Association of America (a rating often associated solely with pornography though that wasn’t necessarily always the case) and it caused some controversy at the time (and would likely do so even more today) for its frank discussions and depictions of sex, violence, racism and drug use.

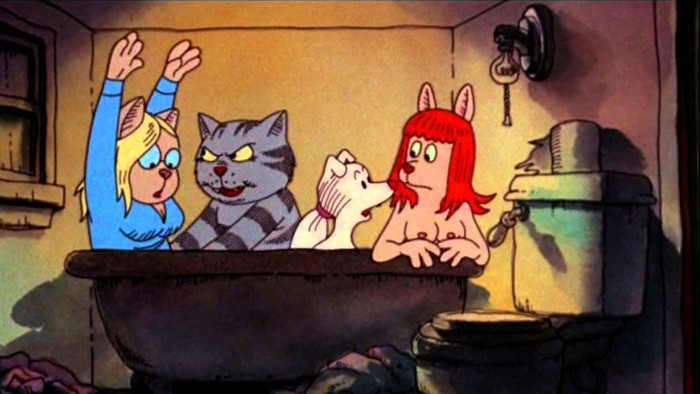

There’s not all that much of a story in truth, just a wild series of happenings (man) that chart the misadventures of Fritz the eponymous feline. At some unspecified point in the late 1960s, a group of hippies gather at Washington Square Park in Manhattan for a protest and the student Fritz the Cat (voiced by Skip Hinnant) and his friends show up hoping to meet girls. They’re attracted to three young women but they seem more interested in a black crow though Fritz eventually convinces the girls to join him in an orgy at a drug den. Fritz decides that the time has come to give up his studies and finds his way to Harlem where he meets Duke the Crow (an uncredited Charles Spidar). They steal a car and drive to the apartment owned by drug dealer Big Bertha (Rosetta LeNoire) whose cannabis joints not only make Fritz very horny but turn him on to the idea of revolution. After inciting a riot his older fox girlfriend, Winston Schwartz (Judy Engles) takes him on a road trip to San Francisco but he falls in with Blue (John McCurry), a methamphetamine-addicted Nazi rabbit biker and a revolutionary lizard named John (McCurry again). Fritz is encouraged to strike a blow against the Man by helping to blow up a power station – and when he changes his mind, it might just be too late…

Today, Fritz the Cat looks very much like the time capsule it is, a film that only have been made in the early 70s (work began on the film in 1970), in the drugged-up wake of the counterculture. Bakshi intended the film to be a satire, as Crumb’s original comics were, but time has blunted the satire to the point where today some of it seems incomprehensible, much of it is tiresome and some even potentially offensive to some. Some of it is just too on the nose to be raise much more than a weary sigh – the police, for example, are deeply stupid pigs (literally). Although some of the issues it tackles so uncompromisingly are still as pertinent as ever, the way in which those issues are tackled today is very different to more forthright and frankly unsubtle way it was back then. It takes satirical swipes at everything from white liberalism to neo-Nazi extremism, giving pseudo-intellectualism a good drubbing along the way.

It plays as very much the anti-Disney – at one point the silhouettes of Mickey Mouse, Daisy Duck and Donald Duck can be seen cheering on a United States Air Force napalm attack on a black neighbourhood and there’s a jokey reference to the Pink Elephants on Parade scene from Dumbo (1941)), a street-level slice of life the likes of which wouldn’t have been allowed anywhere near Disney’s animation rooms. There are no virtuous princesses, no hardy heroes overcoming all obstacles and although there’s an ending that Bakshi hadn’t originally wanted it’s far from a conventionally happy one (he’d originally wanted Fritz to die in the power plant explosion).

Buttons are pressed all over the place. It’s a film very much guaranteed to upset, offend or annoy just about everyone at some point with its confrontational approach to its subject and its tendency to stereotype for comic effect. At the time, it was a hit as it was aimed at an audience that wasn’t being served by animation at the time but today, it feels forced, like it’s trying a bit too hard to shock.

There’s no denying that it’s a historically important film, but like so many historically important films, it isn’t really all that great. There’s a lot here to admire but just as much that will leave you feeling underwhelmed and wondering what early 70s audiences actually saw in it. It’s important now for being the start of Bakshi’s career and for opening the door for more American animated films aimed at an adult audience – as such, it proved that there was more to feature length animation than Disney who had largely ruled the roost in Hollywood for many years. It was certainly a big enough hit in 1972 to warrant a sequel, The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat, which followed in 1974 though of the key creatives involved in Fritz the Cat, only producer Steve Krantz and Fritz’s voice actor Skip Hinnant were involved, Bakshi and Crumb having declined to take part.