This under-appreciated B-chiller from Universal is a far cry from the classics of the 1930s, but it’s still a rather enjoyable little mad scientist film in the fashion of those being made on poverty row by PRC, Monogram and Republic. Its wacky plot can lay claim to featuring Universal’s only zombie and although it’s a very humble film, it’s more enjoyable than one might have expected.

Dr Alfred Morris (George Zucco on good form) is researching the Mayan and has chanced upon their use of a form of nerve gas during rituals of human dissection to appease their gods. He’s assisted by medical student Ted Allison (David Bruce) on using the gas to revive dead animals, a procedure that also calls for the heart of a recently deceased creature of the same species. Ted is distracted by his love for opera singer girlfriend Isabel Lewis (Evelyn Ankers), blissfully unaware that Morris has also fallen for. The manipulative Morris persuades Isabel to leave Ted, hoping to begin a relationship with her himself, unaware that she’s secretly in love with pianist Eric Iverson (Turhan Bey). He uses the nerve gas on Ted, effectively killing him but keeping him in a state of undeath through heart transplants, the organs stolen from freshly buried corpses in local graveyards. Ted is still devoted to Isabel and Morris tries to use him in his ghoul state to murder Iverson. The police and reporter “Scoop” McClure (Robert Armstrong) realize that the “ghoul”-style killings are all happening wherever Isabel’s latest tour takes her and are soon closing in on the killers.

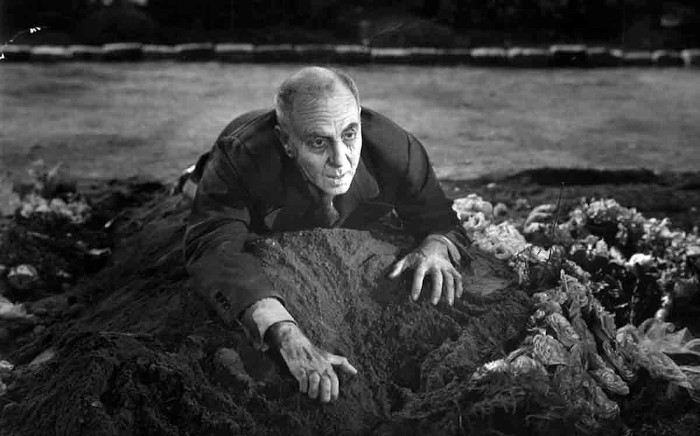

It’s predictable stuff really, but it’s smartly written, nicely acted (Zucco could play this sort of role in his sleep, but he still brings his “A” game) and at times, impressively directed by James Hogan. A prolific director of action films and crime thrillers, this would be Hogan’s final gig – he was dead from a heart attack at the age of just 53 eight days before The Mad Ghoul opened in cinemas on a double bill with Son of Dracula (1943). He brings occasional flashes of a pleasingly grim atmosphere to the proceedings (aided by Milton Krasner’s photography), never more so than in the film’s final shot of Morris, now affected by his own gas, frantically clawing at the dirt in a graveyard before dying.

As noted, Zucco is great, Ankers again doesn’t get as much to do as we’d like, and Bruce makes for a strangely personable zombie. You’ll shed no tears for him, but he’s a sympathetic “monster,” his performance aided no end by Jack P. Pierce’s subtle and understated make-up. Bey was still very early in his career but already showing the charisma that should have made him a bigger star had he been able to escape the grip of the B-movies.

There are issues with the film, not least of which being the surfeit of light operetta scenes, a problem it shares with the subsequent The Climax (1944) which, like The Mad Ghoul, was also filmed on the standing sets left over from the 1925 The Phantom of the Opera and also featured Bey in a very similar role. The songs are undistinguished and eminently fast-forwardable – Ankers was disappointed that she wasn’t allowed, due to time constraints, to perform the songs herself and had to mime to recordings of Lillian Cornell instead. The romantic triangle business isn’t terribly convincing either come to that.

But there’s a wonderful darkness to it all, the script full of Production Code-baiting nastiness that mostly happens off camera, but which is still surprisingly effective. Bodies are dug up and mutilated, test animals killed, and meddling reporters brutally stabbed in the neck. The latter is meant as the film’s comic relief so his demise – after faking his own death and sitting up in a coffin – is all the more shocking.

The Mad Ghoul is, for want of a better word, hokum, but it’s entertaining and has some small depth to it. The script seems to be saying something about human fear of endings, be it life itself, relationships or academic failure. It’s not deep exactly, but there’s a sense of writers Paul Gangelin and Brenda Weisberg at least trying to do something a bit clever, even if the restrictions of the B-movie format (and the catchpenny title, reduced from the shooting script’s The Mystery of the Mad Ghoul) largely batter them into submission. Top marks for trying though.

The Mad Ghoul, to a degree, gives lie to the idea that all post-The Wolf Man (1941) horrors were all worthless. It’s not the greatest film in their line of monster films but it’s a decent, hugely entertaining bit of nonsense that should keep all but the most critical of viewers pleased for its brief 65 minutes. Universal had vague plans for a “monster rally” to be titled Chamber of Horrors around the time of the film’s release that would have united all their big horror stars and characters. The Mad Ghoul was mentioned in trade journals as being part of that menagerie, but the film was never made and when Universal did make their all-star monster meet-up, House of Frankenstein (1944), poor old Ted remained unexhumed and conspicuous by his absence.